Libri antichi e moderni

RIDOLFI, Lucantonio

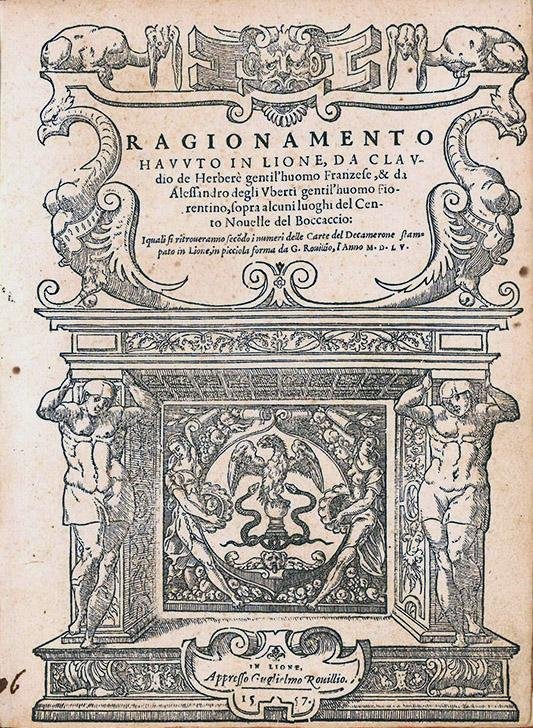

Ragionamento havuto in Lione, da Claudio de Herberé gentil'huomo franzese, et da Alessandro degli Uberti gentil'huomo fiorentino, sopra alcuni luoghi del Cento novelle di Boccaccio, i quali si ritroveranno secondo i numeri delle carte del Decamerone stampato in Lione, in picciola forma da G. Rovillo

Guillaume Rouillé, 1557

1350,00 €

Govi Libreria Antiquaria

(Modena, Italia)

Le corrette spese di spedizione vengono calcolate una volta inserito l’indirizzo di spedizione durante la creazione dell’ordine. A discrezione del Venditore sono disponibili una o più modalità di consegna: Standard, Express, Economy, Ritiro in negozio.

Condizioni di spedizione della Libreria:

Per prodotti con prezzo superiore a 300€ è possibile richiedere un piano rateale a Maremagnum. È possibile effettuare il pagamento con Carta del Docente, 18App, Pubblica Amministrazione.

I tempi di evasione sono stimati in base ai tempi di spedizione della libreria e di consegna da parte del vettore. In caso di fermo doganale, si potrebbero verificare dei ritardi nella consegna. Gli eventuali oneri doganali sono a carico del destinatario.

Clicca per maggiori informazioniMetodi di Pagamento

- PayPal

- Carta di Credito

- Bonifico Bancario

-

-

Scopri come utilizzare

il tuo bonus Carta del Docente -

Scopri come utilizzare

il tuo bonus 18App

Dettagli

Descrizione

RARE FIRST EDITION (it was reprinted in 1558 and in 1560). The publisher Guillaume Rouillé (1518?-1588), who, starting with an Italian translation of De viris illustribus urbis Romae, published at the Sign of Venice in Lyons during his life over seventy book in Italian. These were addressed not only to the Italians residing in France, but also to the many Frenchmen, who had learned Italian in the course of war, study, or business. Rouillé had apprehended the book business in Venice with Giovanni and Gabriello Giolito and established himself at Lyons in 1543. His book production exceeded that of Robert Estienne, Gryphius and de Tournes, and his learning at least equalled theirs. His firm gained European reputation and his books were also sold in Antwerp, Frankfurt, Medina del Campo, Saragossa, as well as in Venice and Naples (cf. N. Zemon Davis, Publisher Guillaume Rouillé, Businessman and Humanist, in: “Editing Sixteenth Century Texts. Papers given at the Editorial Conference University of Toronto”, R.J. Schoeck, ed., Toronto, 1966, pp. 72-112; see also J. Balsamo, L'italianisme lyonnais et l'illustration de la langue française, in: “Lyon et l'illustration de la langue française à la Renaissance”, Lyon, 2003, pp. 211-229).

Rouillé dedicated his Decamerone to Marguerite du Bourg, dame du Cange, wife of a high French financial officer, a very learned lady, to whom he was later to dedicate also his 1558-edition of Petrarch (cf. M.-M. Fontaine, ‘Un couer mis en gage'. Pontus de Tyard, Marguerite du Bourg et le milieu lyonnais des années 1550, in: “Nouvelle Revue du XVIe siècle”, 1984/2, p. 76-77; see also É. Picot, Les français italianisants au XVIe siècle, Paris, 1906, I, pp. 201-202).

“Il Ridolfi, che collaborò con il Rouillé anche all'edizione del Petrarca (1550) e pubblicò presso lo stesso editore il dialogo l'Aretefila (1560), contribuì con una Vita di M. Giovanni Boccaccio brevemente descritta e con il Raccoglimento di tutte le sentenze a quella che viene considerata come la prima edizione stampata in Francia del Decameron in lingua italiana, la quale uscì dai torchi del Rouillé in formato tascabile nel 1555” (cfr. E. Giudici, Luc'Antonio Ridolfi et la Renaissance Franco-Italienne, in: “Quaderni di Filo- logia e Lingue Romanze”, n.s. 1, Rome, 1985, pp. 115-150).

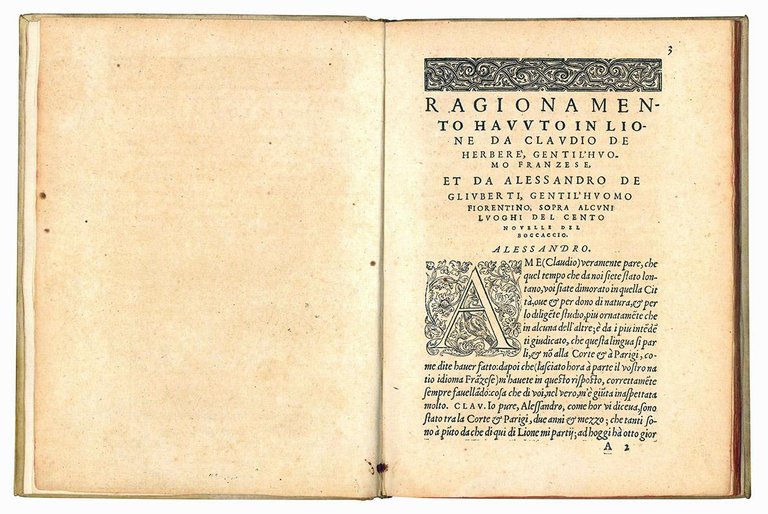

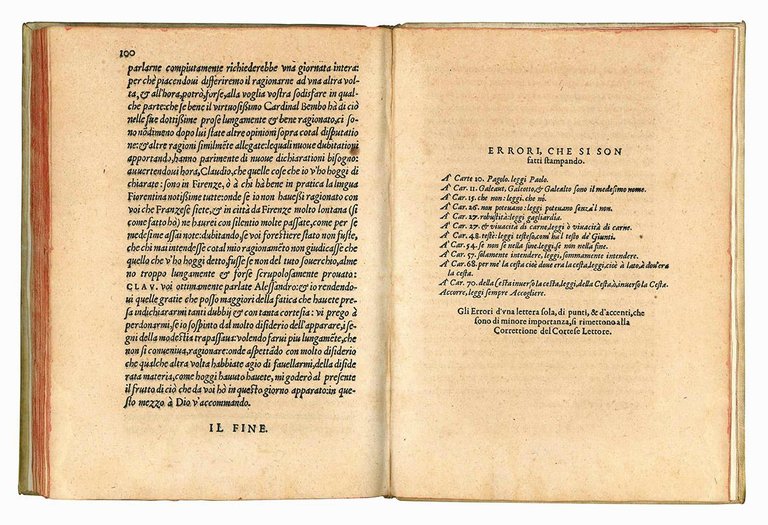

As clearly can also be presumed from the title, the Ragionamento is intended as a page by page commentary to Rouillé's edition of the Decamerone. “Le text est anonyme, mais il est sûrement de Ridolfi, ainsi qu'en témoigne une lettre de son ami Alfonso Cambi. Herberé est un Français féru d'italien, qui a été inspiré par un séjour de deux ans dans le cercle de Marguerite de Berry, où tous cultivent le toscan. Herberé cherche à perfectionner son italien à l'aide du Décaméron, et se met à interroger Degli Uberti sur le text. Ce Degli Uberti est basé probablement sur quelque parent d'Antonio di Niccolò degli Uberti, éditeur du Décaméron en 1527, mais ce qu'il dit reflète les opinions de Ridolfi lui-même, qui n'oublie pas quelques allusions désobligeantes sur d'autres éditeurs, dont Girolamo Ruscelli (Venise 1552). Ces allusions valurent à Ridolfi quelques médisances de la part d'autres exilés florentins, dont Ludovico Castelvetro dans une lettre à Francsco Giuntini. Mais l'intérêt du dialogue réside dans ce qu'il nous apprend sur la fortune en France de Boccace, ainse que dans les multiples allusions dans le text à la Divina Commedia” (R. Cooper, Le cercle de Lucantonio Ridolfi, in: “L'émergence littéraire des femmes à Lyon à la Renaissance, 1520-1560”, M. Clément & J. Icadorna, eds., Saint-Étienne, 2008, p. 43).

“Lucantonio Ridolfi publie également chez Guillaume Rouillé des dialogues qui mettent e