Libri antichi e moderni

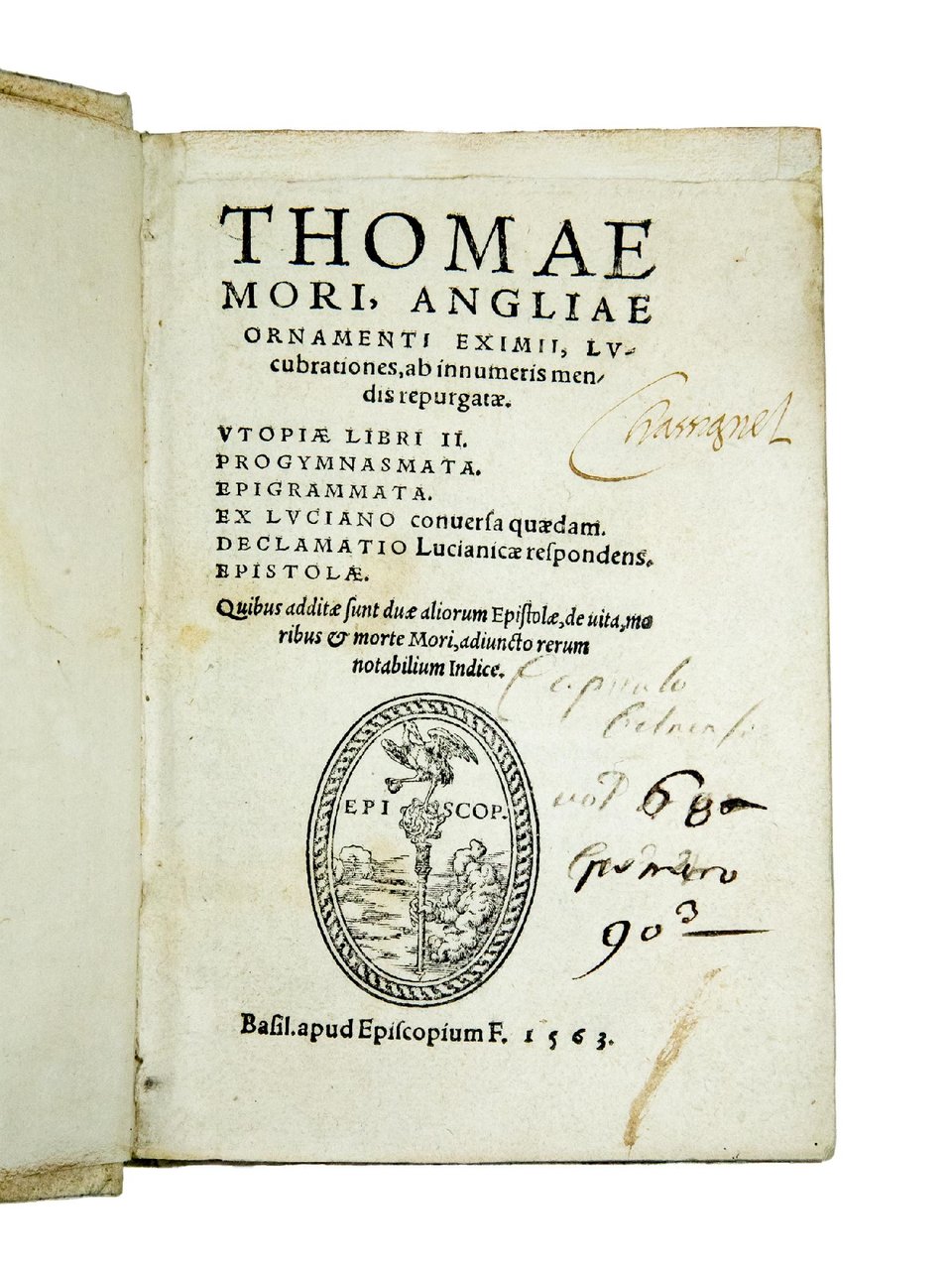

MORE, Thomas (1478-1535)

Lucubrationes, ab innumeris mendis repurgatae. Utopiae libri II. Progymnasmata. Epigrammata. Ex Luciano conversa quaedam. Declamatio Lucianicae respondens. Epistolae. Quibus additae sunt duae aliorum Epistolae, de vita, moribus et morte Mori, adiuncto rerum notabilium Indice

Nikolaus Episcopius, 1563

2800,00 €

Govi Libreria Antiquaria

(Modena, Italia)

Le corrette spese di spedizione vengono calcolate una volta inserito l’indirizzo di spedizione durante la creazione dell’ordine. A discrezione del Venditore sono disponibili una o più modalità di consegna: Standard, Express, Economy, Ritiro in negozio.

Condizioni di spedizione della Libreria:

Per prodotti con prezzo superiore a 300€ è possibile richiedere un piano rateale a Maremagnum. È possibile effettuare il pagamento con Carta del Docente, 18App, Pubblica Amministrazione.

I tempi di evasione sono stimati in base ai tempi di spedizione della libreria e di consegna da parte del vettore. In caso di fermo doganale, si potrebbero verificare dei ritardi nella consegna. Gli eventuali oneri doganali sono a carico del destinatario.

Clicca per maggiori informazioniMetodi di Pagamento

- PayPal

- Carta di Credito

- Bonifico Bancario

-

-

Scopri come utilizzare

il tuo bonus Carta del Docente -

Scopri come utilizzare

il tuo bonus 18App

Dettagli

Descrizione

Adams, M-1752; VD 16, M-6302; R.W. Gibson, St. Thomas More: a Preliminary Bibliography of his Works and Moreana to the Year 1700, (Hamden, CT, 1977), no. 74; Th. More, The Correspondence, E.F. Rogers, ed., (Princeton, NJ, 1947), pp. XV-XXII; B.J. Trapp & H. Schulte-Herbrüggen, ‘The King's Good Servant': Sir Thomas More, Exhibition Catalogue, (London, 1977), p. 133, no. 261.

FIRST COLLECTED EDITION of Thomas More's Latin works, in which are printed for the first time some of his letters.

The volume includes the two books of Utopia with the usual prefatory letters by Erasmus, Guillaume Budé, Pieter Gillis, and by More himself; More's and Lily's Progymnasmata; the Latin epigrams; More's translation of the dialogues of Lucian, along with his Declamatio in response to the latter; 13 letters by More, 1 letter addressed by Erasmus to Ulrich von Hutten on More's life, and 1 letter on More's death generally attributed to Gilbert Cousin, Philippus Montanus, and Eramsus himself.

Among More's letters stands out the famous long letter to Martin Dorp at Louvain dated October 21, 1515 (pp. 365-428), which is, in fact, a vindication of the ‘new learning', and a clear statement of More's intellectual credo. He considered the study of the Greek text of the New Testament much more desirable than the blind acceptance of the Vulgate. This statement was of considerable importance for the development of humanism and of Western thought generally (cf. J.H. Bentley, New Testament Scholarship at Louvain in the Early Sixteenth Century, in: “Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History”, new series, II, 1979, pp. 53-79).

Erasmus' letter to Hutten (pp. 497-510; cf. P.S. Allen, ed., Opus epistolarum Des. Erasmi, Oxford, 1922, IV, no. 999, pp. 12-23), first published in his Farrago nova epistolarum (Basel, 1519), gives a biography of More and a detailed description of his physical appearance. The final letter (pp. 511-530), signed by Covrinus Nucerinus (clearly a pseudonym) and addressed to Philippus Montanus, a pupil of Erasmus, is concerned with More's trial and execution. It had appeared for the first time without place of publication and printer's name, but had actually been printed by Hieronymus Froben in Basel in 1535 (cf. P.S. Allen, ed., Opus epistolarum Des. Erasmi, Oxford, 1947, XI, app. XXVII, pp. 368-378).

“Only ninety-three of More's Latin letters (among them four written under pseudonyms) survive, counting the familiar, the public, and everything in between […] Some of More's letters were suppressed, lost, or destroyed for political reasons, which makes the recent discovery of a manuscript bundle that belonged to Frans van Cranevelt and includes seven hitherto unknown letters by More an extraordinary event. But More himself, in this respect unlike Erasmus, does not seem to have tried to publish his letters (or have them published) as a collection, although clearly he kept copies. In fact, on occasion he withheld publication. In 1520, for instance, he wrote William Budé and asked him not to publish his letters to him, at least until he had revised them, […] In any case, More's situation differed from someone like Erasmus, despite his connections with him. More wrote some of his best-known familiar letters (and most of his official letters) in English, not Latin. Additionally, he was a busy lawyer, judge, administrator, and statesman; humanism was never the whole of his life, and his projections of self and life are multiple, even disparate. To put this another way, More depended much less than Erasmus did upon representing himself as a man of letters, although he was attracted to that sort of life. In fact only twenty-four of More's letters were published – that is, printed – during his lifetime, a