Libri antichi e moderni

LIPSIUS, Justus (1547-1606)

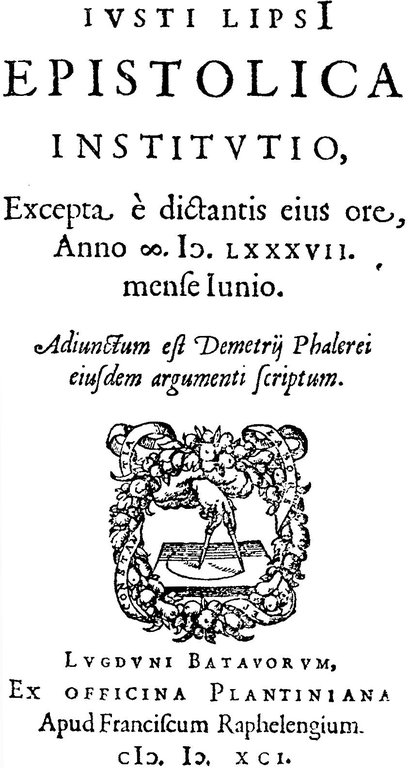

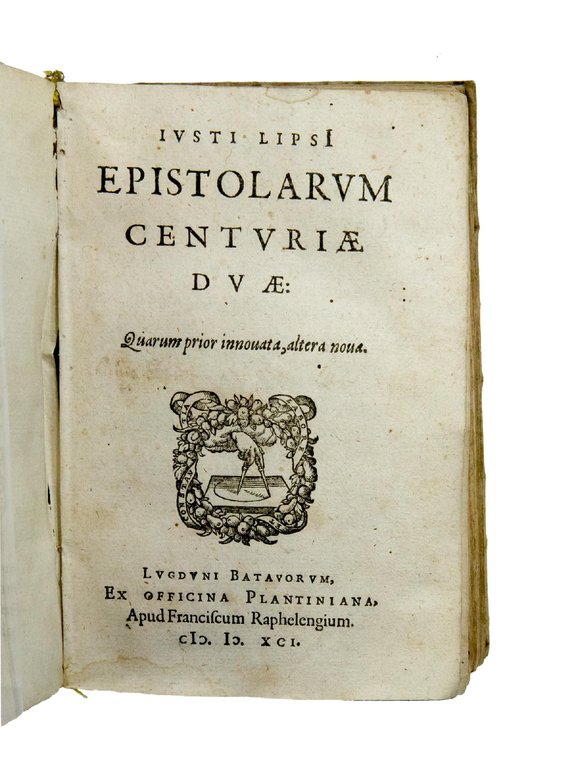

Epistolica institutio, Exepta è dictantis eius ore, Anno M.D. LXXXVII. Mense Iunio. Adiunctuum est Demetrij Phalerei eiusdem argumentum scriptum. [bound with:] Epistolarum centuriae duo. Leiden, Ex officina Plantiniana, Apud Franciscum Raphelengium, 1591.

Franciscus Raphelengius, 1591

1200,00 €

Govi Libreria Antiquaria

(Modena, Italia)

Le corrette spese di spedizione vengono calcolate una volta inserito l’indirizzo di spedizione durante la creazione dell’ordine. A discrezione del Venditore sono disponibili una o più modalità di consegna: Standard, Express, Economy, Ritiro in negozio.

Condizioni di spedizione della Libreria:

Per prodotti con prezzo superiore a 300€ è possibile richiedere un piano rateale a Maremagnum. È possibile effettuare il pagamento con Carta del Docente, 18App, Pubblica Amministrazione.

I tempi di evasione sono stimati in base ai tempi di spedizione della libreria e di consegna da parte del vettore. In caso di fermo doganale, si potrebbero verificare dei ritardi nella consegna. Gli eventuali oneri doganali sono a carico del destinatario.

Clicca per maggiori informazioniMetodi di Pagamento

- PayPal

- Carta di Credito

- Bonifico Bancario

-

-

Scopri come utilizzare

il tuo bonus Carta del Docente -

Scopri come utilizzare

il tuo bonus 18App

Dettagli

Descrizione

I. EPISTOLICA INSTITUTIO:

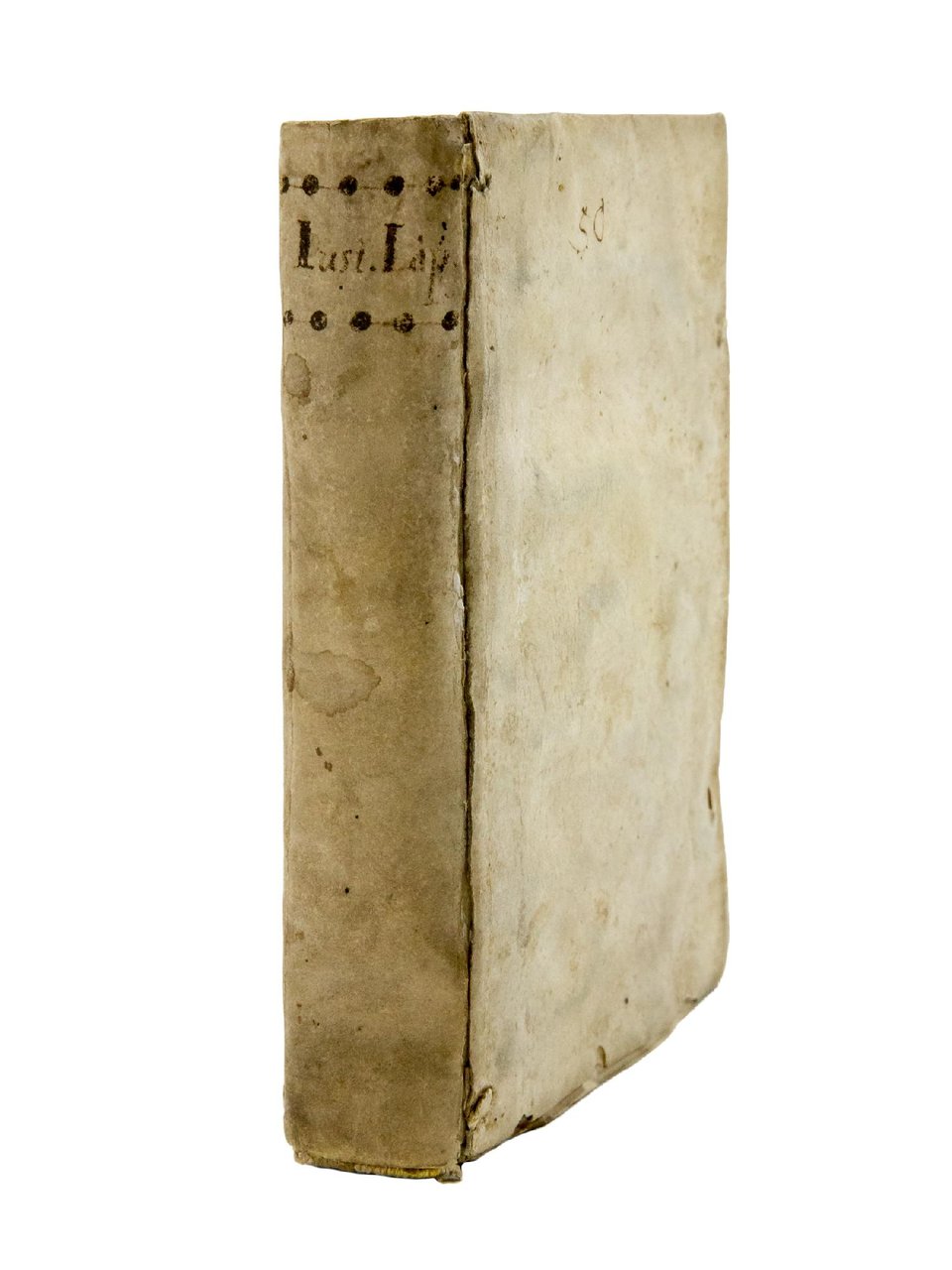

44, (4) pp. A-C8 (C7 and C8 are blank). With the printer's device on the title page. Contemporary vellum with inked title on spine.

Green & Murphy, p. 275; Gueudet, pp. 370-371; J. Rice Henderson, Humanist Letter Writing: Private Conversation or Public Forum?, in: “Self-presentation and Social Identification. The Rhetoric and Pragmatics of Letter Writing in Early Modern Times”, T. Van Houdt, J. Papy, G. Tournoy & C. Matheeleussen, eds., (Leuven, 2002), p. 37.

ORIGINAL EDITION (a quarto edition with different pagination was simultaneously issued by the same printer) of Lipsius' letter-writing manual originated from a lecture held in June 1587. To Lipsius' treatise is appended a bi-lingual edition of Demetrius' description of the classical familiar letter. The work was reissued in 1601, again in quarto and in octavo, and in 1605, in quarto only. These editions are the only printings of the work during the author's lifetime that he supervised. Until the end of the century the work was also printed in other countries, evidently without Lipsius' authorization, first at Frankfurt/M. (1591) and then at Lyon (1592, 1596), Magdeburg (1594), Cologne (1596, 1597), and Paris (1599) (cf. Justus Lipsius, Principles of Letter-Writing: A Bilingual Text of ‘Justi Lipsii Epistolica Institutio', R.V. Young & M.T. Hester, eds., Carbondale, IL, 1996, pp. xlviii-il).

“In 1591 Lipsius allowed Raphelengius to publish his Epistolica Institutio, which in its sixteen printed leaves completed the liberation of epistolography from the rules of rhetoric. His recommendations are generally models of brevity and lucidity, composed according to the principles established by his predecessors, in particular Vives, whose interest in the psychology of the writers of letters and their recipients found a sympathetic response in Lipsius. He did not need the rules of Francesco Negri, nor even of Erasmus and Vives” (M. Morford, Lipsius' Letters of Recommendation, in: “Self-presentation and Social Identification. The Rhetoric and Pragmatics of Letter Writing in Early Modern Times”, T. Van Houdt, J. Papy, G. Tournoy & C. Matheeleussen, eds., Leuven, 2002, p. 189).

“Lipsius clearly devoted the first ten chapters of his Institutio to the epistolary ars; the last three may be regarded as personal admonitions to the artifex [...] ‘graded' for the youthful, the more mature, and the adult student, and departing progressively from Ciceronian basis recommended to the first group. There are also admonitions for keeping a notebook or commonplace book in the Renaissance manner. Such material belongs under the caption of artifex and thus entitles the 0 to placement in the isagogic category by its principle to structure as much as by its address to the young [...] Lipsius attempted to drive a sharp wedge between the letter, properly so called, and other written communications which had long borne the name of letter incorrectly. He made a threefold division of letters according to subject matter: ‘materies seria', ‘materies docta', and ‘materies familiaris'. The first dealt with public or private matters of gravity, the second with technical or learned questions. If I interpret him correctly, he regarded the first essentially an oration, the other essentially a treatise. He then turned to the genuine letter, the ‘materies familiaris' designating it by the adjective ‘propria'. Of this type of subject his says: ‘Denique familiarem dico, quae res tangit nostras aut circa nos, quaeque in assidua vita. Ea propria et creberrima Epistolae materies: &, si verum fateri volumus, germanaem illius una'. Having limited the genuine letter to the familiar kind, Lipsius proceeded to detach it more definitely from oratorical associations evident in the Renaissance epistolary manuals. In Chapter VI of the Institutio, for all practical purposes, he rejects for the letter the first two parts of traditional rhetoric, viz. invent