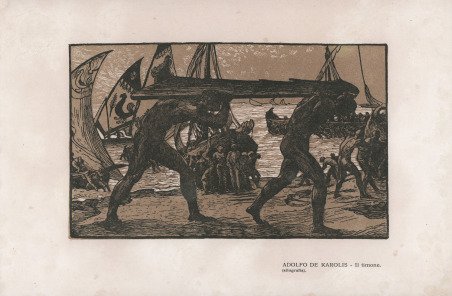

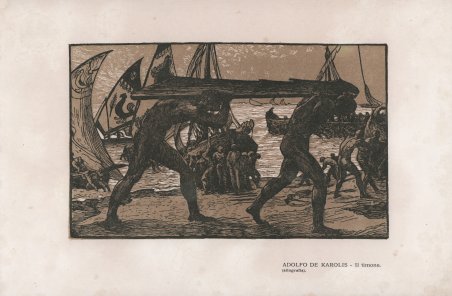

Xilografia a due legni, 1908, priva di firma. Impressione eccellente su carta avorio liscia. Ottimo stato di conservazione. Ampi margini oltre la linea marginale. Nel primo decennio del 1900, De Carolis dedica molta attenzione alla rievocazione di temi popolari, legati in particolare alle raffigurazioni di marine, così come testimonia questa stampa. L'utilizzo di più colori e quindi di un numero maggiore di legni ben si adatta alla vivacità di questi soggetti. Dopo l'adesione nel '96 al gruppo romano ' In arte libertas, ' creato dal paesista Nino Costa, dal 1901 insegna ornato in accademia nella Firenze dei maestri del Rinascimento, del "terribile" Michelangelo, del Böcklin dell'Isola dei morti. Comincia ad ornare libri per D'Annunzio e Pascoli e dal 1903 elabora fregi e d articoli per la rivista "Leonardo" fondata con Papini e Prezzolini. ' Fra le rigogliose figurazioni per la Francesca da Rimini (1902), le rusticane de La figlia di Iorio (1904), le lapidarie del Notturno del "Vate" (1917-21), le stampe marinaresche esprimono un'autonoma poetica. Il varo, L'argano, Il timone, La foce, Le arche - xilografie eseguite fra il 1904 e il 1908, mentre in Europa esplodono primi fenomeni d'avanguardia - denotano un lirismo contemplativo invischiato nel ristagno simbolista che connota la situazione italiana all'avvio del secolo. Ma al di là dei convenzionali significati latenti, quelli manifesti aprono - pur aderendo al fervore estetico del giapponismo fin-de-siècle - un discorso etnografico che si fa via via più urgente, teso a documentare l'irripetibile patrimonio che la "novella civiltà livellatrice" viene annientando. L'appello del 1920 (L'arte popolare, in "La Fionda", Roma) riscuote entusiastiche risposte, stimolando una sensibilità che nel 1923 porta all'istituzione del Regio Museo di etnografia italiana, dal 1956 Museo Nazionale delle Arti e Tradizioni popolari. Woodcut, 1908, ' printed from two blocks. Excellent impression, printed on ivory paper, wide margins, good condition. De Carolis was an artistic polymath, working as a painter (in particular of murals), interior designer, decorator, xylographer (wood engraver), illustrator and photographer, and is probably the best known exponent of Art Nouveau in Italy. His talent and originality was quickly recognised by two of the greatest Italian writers and poets of the day, Gabriele D'Annunzio and Giovanni Pascoli, and he became their preferred illustrator. Among his most popular works were many illustrations for ' Gabriele d'Annunzio's novels (Il Notturno, ' La figlia di Jorio) and ' Giovanni Pascoli‘s books of poems. In the first decade of the 1900s, De Carolis devoted a great deal of attention to the evocation of popular themes, linked in particular to representations of seascapes, as this print testifies. The use of more colors and therefore a greater number of woods is well suited to the liveliness of these subjects. After joining in '96 the Roman group In arte libertas, created by the landscape painter Nino Costa, from 1901 he taught ornament in the academy in Florence of the Renaissance masters, of the "terrible" Michelangelo, of Böcklin of the Isle of the Dead. He began to decorate books for D'Annunzio and Pascoli and since 1903 elaborates friezes and articles for the magazine "Leonardo" founded with Papini and Prezzolini. ' Among the luxuriant figurations for the Francesca da Rimini (1902), the rusticane of The daughter of Iorio (1904), the lapidarie of the Nocturne of the "Vate" (1917-21), the prints marinaresche express an autonomous poetic. Il varo, L'argano, Il timone, La foce, Le arche - woodcuts made between 1904 and 1908, while the first avant-garde phenomena were exploding in Europe - denote a contemplative lyricism caught up in the symbolist stagnation that characterized the Italian situation at the beginning of the century. But beyond the conventional latent meanings, the manifest ones open - while adhering to the aesthetic fervor of Japanism fin-de-siècle - an ethnographic discourse that becomes more and more urgent, aimed at documenting the unique heritage that the "new leveling civilization" is annihilating. The appeal of 1920 (L'arte popolare, in "La Fionda", Rome) received an enthusiastic response, stimulating a sensitivity that in 1923 led to the establishment of the Royal Museum of Italian Ethnography, since 1956 the National Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions. Cfr.

Découvrez comment utiliser

Découvrez comment utiliser