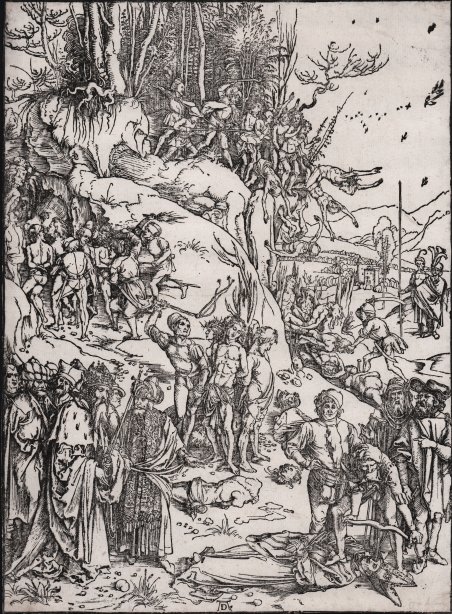

Il martirio dei diecimila

Mode de Paiement

- PayPal

- Carte bancaire

- Virement bancaire

- Pubblica amministrazione

- Carta del Docente

Détails

- Année

- 1496

- Format

- 285 X 390

- Graveurs

- DURER Albrecht

Description

Il martirio di diecimila cristiani, sullo sfondo soldati che inseguono prigionieri sul ciglio di una rupe, al centro la tortura di un gruppo di prigionieri legati a un albero, circondati da parti del corpo smembrate, in primo piano a destra, un vescovo viene infilzato nell'occhio destro, a sinistra un gruppo di persone che assiste al martirio. Xilografia, 1496 circa, firmata con il monogramma AD in basso al centro. Buona impressione della sesta variante di sette descritta da Meder (f /g), stampata su carta vergata con filigrana "Piccolo Stemma con Croce" (Meder 151), completa della linea marginale, in ottimo stato di conservazione. Il Martirio dei diecimila è una delle prime grandi xilografie prodotte dal Maestro di Norimberga, relativa ad una decade di intenso impegno nell’intaglio (1496/1505) che lo portò tra l’altro ad incidere le tavole dell’Apocalisse, stilisticamente molto simili a questa. Il tema è molto affascinante: “Non è dato sapere se l'idea di una xilografia di questo raccapricciante soggetto sia stata di Dürer o se gli sia stata suggerita dal duca di Sassonia Frederick the Wise (Federico il Saggio), che soggiornò a Norimberga dal 14 al 18 aprile del 1496. In ogni caso, il duca rimase talmente affascinato dal soggetto che commissionò a Dürer di dipingerlo su un pannello (ora trasferito su tela) di 99 x 87 cm per la nuova Schlosskirche di Wittenberg nel 1508. La storia del martirio di diecimila cristiani compari per la prima volta nella letteratura del XII secolo, soprattutto in Germania e in Svizzera. È raccontata da Voragine nel supplemento alla Legenda Aurea e nel 1472 è stata inclusa nell'edizione di Günther Zainer del Passional oder der Heiligen Leben. Un dipinto di questo soggetto era a disposizione di Dürer anche a Norimberga, nella Augustinerkirche, realizzato dal Maestro della Pala di Sant'Agostino. Tuttavia, la figura prominente del vescovo a cui viene cavato l’occhio in primo piano nella xilografia, è assente dal dipinto. Compare, invece, in una tela del primo Quattrocento con lo stesso soggetto, proveniente dalla bassa valle del Reno e oggi conservata a Colonia. Per la composizione di questo foglio a più figure, Dürer sembra essersi ispirato al "rogo delle reliquie di Giovanni Battista" di Geertgen tot Sint Jans, che si trovava ad Haarlem al tempo. L'opera, che si trova ora a Vienna, avvalora l'ipotesi che Dürer abbia visitato i Paesi Bassi durante i suoi viaggi come apprendista. L'influenza di Mantegna si nota nel gruppo di tre martiri che vengono frustati al centro. La figura centrale è simile a quella di Cristo nella Flagellazione di Martina Schongauer (B.12). Il torso decapitato a terra ha una certa somiglianza con i disegni di un antico marmo della Casa Sassi a Roma, che Dirck Volckertsz Coornhert ritenne abbastanza importante da incidere nel 1553. Rupprich cita questo busto come prova che Dürer visitò Roma durante il suo viaggio italiano del 1494-95. Il gruppo a sinistra è stato identificato come l'imperatore romano Adriano (117-138 d.C.) con diversi potenti orientali, il più importante dei quali sarebbe Sapor II di Persia. Il vescovo torturato a destra è stato identificato come Sant’Acacio. Secondo una leggenda, l'imperatore Adriano aveva stipulato un contratto con il principe pagano Acacio per aiutarlo durante una spedizione militare in Asia Minore con un esercito di 9000 uomini. Durante la marcia verso la battaglia, diversi angeli apparvero alle truppe incoraggiandole a essere coraggiose nonostante la superiorità numerica del nemico e assicurando loro la vittoria. Dopo il successo, gli angeli riapparvero e ordinarono agli uomini di recarsi sul monte Ararat dove abbracciarono il cristianesimo. Alla notizia della loro conversione, l'infuriato Adriano ordinò di ucciderli tutti. Durante il martirio, altri mille uomini si unirono a loro in segno di ammirazione. In conformità con questa storia, il dipinto della predella a Norimberga . The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand Christians, in the background soldiers chase prisoners over a cliff edge, in the middleground the torture of a group of prisoners tied to a tree, surrounded by body parts, in the right foreground a bishop is drilled into his right eye, on the left a group a people onlooking. Woodcut, circa 1496, signed with monogram at lower center. A good Meder f (of g) impression, printed on laid paper with “Small Coat of Arms with Cross” watermark (Meder 151), complete of the borderline, very good condition. The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand is one of the first major woodcuts produced by the Nuremberg Master, relating to a decade of intense carving endeavor (1496/1505) that led him, among other things, to carved the plates of the Apocalypse, stylistically very similar to this one. The theme is very fascinating: “It is not recorded whether the idea for a woodcut of this gruesome subject was Dürer's own or whether it was perhaps suggested to him by Duke Frederick the Wise of Saxony who stayed at Nuremberg from 14 to 18 April of 1496, at which Occasion Dürer painted the prince's portrait.' In any event, Frederick the Wise was fascinated enough by the subject that he commissioned Dürer to paint it on a panel (now transferred onto canvas) measuring 99 x 87 cm for the new Schlosskirche in Wittenberg in 1508. The story of the martyrdom of ten thousand Christians first appears in literature during the twelfth century, primarily in Germany and Switzerland. It is told by Voragine in the supplement to the Legenda Aurea and in 1472, it was included in Günther Zainer's edition of Passional oder der Heiligen Leben. A painting of this subject was also available to Dürer at Nuremberg in the Augustinerkirche, painted by the Master of the St. Augustine Altarpiece. However, the prominent figure of the bishop, whose eye is being drilled out in the foreground of the woodcut, is notably absent from the painting. It does appear on an early fifteenth century canvas of the subject from the lower Rhine valley, now in Cologne. For the composition of this multi-figured sheet, Dürer seems to have been guided by Geertgen tot Sint Jans' "Burning of the Relics of John the Baptist" which was in Haarlem during Dürer's lifetime. It is now in Vienna and lends credence to the hypothesis that Dürer visited the Netherlands during his travels as a journeyman. The influence of Mantegna has been discerned in the group of three martyrs being whipped in the center. The middle figure is akin to that of Christ in Martin Schongauer's "Flagellation" (B.12).5 The decapitated torso on the ground bears some resemblance to drawings of an antique marble in the Casa Sassi in Rome that was considered important enough by Dirck Volckertsz Coornhert for him to engrave it in 1553. Rupprich cites this torso as evidence that Dürer visited Rome during his Italian journey of 1494-95. The group on the left has been identified as the Roman Emperor Hadrian (AD 117-138) with several oriental potentates, the most prominent one among them supposedly being Sapor II of Persia. The bishop being tortured on the right has been identified as St. Achatius. However, at this point problems arise: according to one legend, the Emperor Hadrian had contracted with the heathen prince Achatius to aid him during a military expedition in Asia Minor with an army of 9000 men. During the march to the battle several angels appeared to the troops encouraging them to be brave in spite of being outnumbered by the enemy and assuring them victory. After their success, the angels reappeared and instructed the men to proceed to Mt. Ararat where they embraced Christianity. Upon hearing of their conversion, the infuriated Hadrian ordered them all killed. During the martyrdom, another thousand men joined them in admiration. In conformity with this story, the predella painting in Nuremberg shows Achatius wearing a ducal cap, not a bishop's mitre. Anzelewski cite. Cfr.