Libros antiguos y modernos

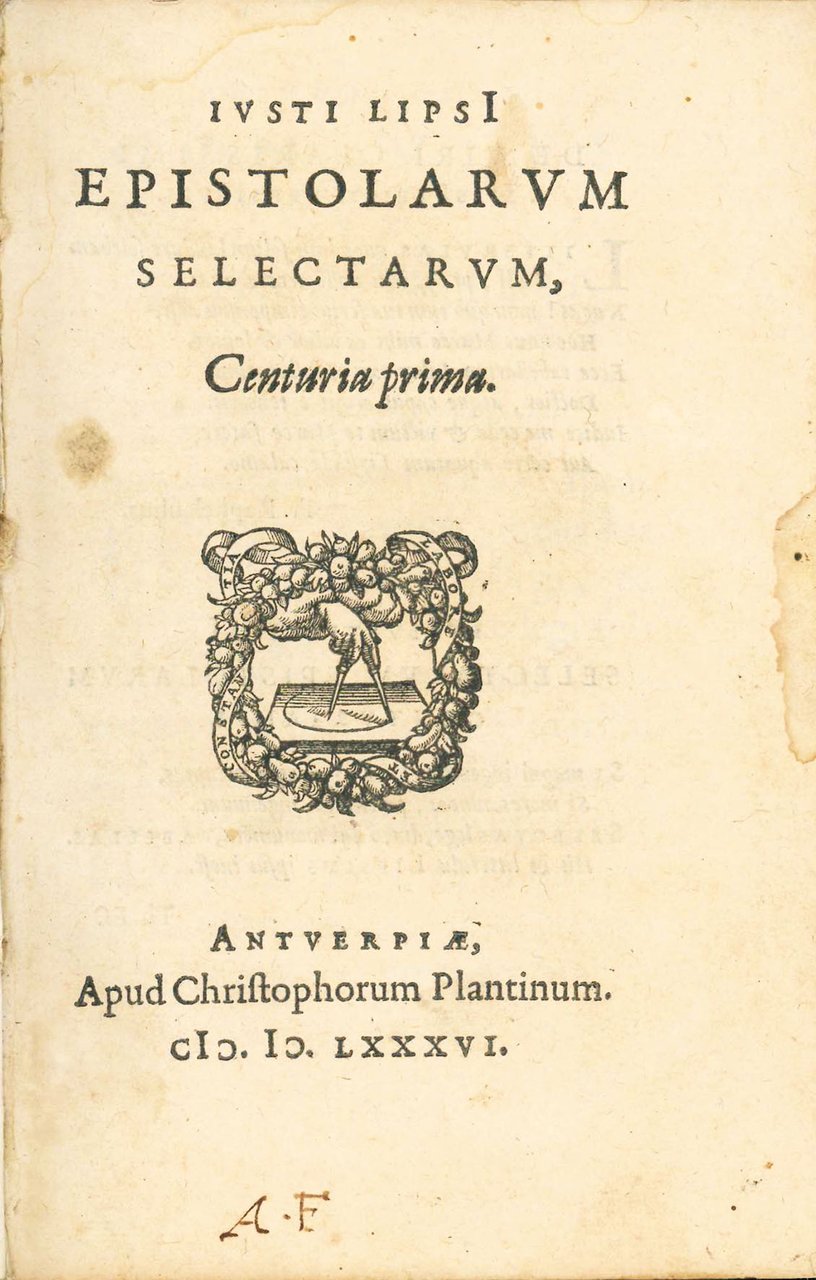

LIPSIUS, Justus (1547-1606)

Epistolarum selectarum, Centuria prima

Christoph Plantin, 1586

900,00 €

Govi Libreria Antiquaria

(Modena, Italia)

Los gastos de envío correctos se calculan una vez añadida la dirección de envío durante la creación del pedido. El vendedor puede elegir uno o varios métodos de envío: standard, express, economy o in store pick-up.

Condiciones de envío de la Librería:

Para los productos con un precio superior a 300 euros, es posible solicitar un plan de pago a plazos al Maremagnum. El pago puede efectuarse con Carta del Docente, Carta della cultura giovani e del merito, Administración Pública.

Los plazos de entrega se estiman en función de los plazos de envío de la librería y del transportista. En caso de retención aduanera, pueden producirse retrasos en la entrega. Los posibles gastos de aduana corren a cargo del destinatario.

Pulsa para saber másFormas de Pago

- PayPal

- Tarjeta de crédito

- Transferencia Bancaria

-

-

Descubre cómo utilizar

tu Carta del Docente -

Descubre cómo utilizar

tu Carta della cultura giovani e del merito

Detalles

Descripción

Adams, L-815; Biblioteca Belgica, L-221; Voet, no. 1543; T. Deneire, “Laconicae cuspidis instar”. The Correspondence of Justus Lipsius: 1598. Critical Edition with an introduction, annotations and stylistic study, (Thesis: Louvain, 2009), p. 13; A. Gerlo, M.A. Nauwelaerts & H.D.L. Vervliet, eds., Iusti Lipsi Epistolae, (Bruxelles, 1978-1983), I, p. 20.

FIRST EDITION (there is also extant a variant with Leiden as printing place, where the volume was actually printed). On October 6, 1585 Lipsius asked Plantin's advice about the dedicatory letter to the volume. Personally he thought of Dirk van Leeuwen, ‘senator' of the Court of Holland and his close friend, but perhaps Plantin had someone else in mind. The work was finally dedicated to the magistrates of the city of Utrecht (Leiden, November 13, 1585).

The volume contains 86 letters by Lipsius and 14 addressed to him (cf. J. Papy, La correspondance de Juste Lipse: genèse et fortune des ‘Epistolarum Selectarum Centuria”, in: “Les Cahiers de l'Humanisme”, 2, 2001, pp. 223-236).

“[...] Juste Lipse, qui fut aussi, comme tous les grands humanists, un épistolier des plus zélés. Plus de 4.300 lettres écrites par Lipse ou lui adressées ont été conservées. Environ 800 lettres d'entre elles ont été publiées de son vivant” (A. Gerlo & H.D.L. Vervliet, Inventaire de la correspondance de Juste Lipse 1564-1606, Antwerp, 1968, p. 5).

“There is an obvious problem with publishing a letter that was originally destined only for one recipient. Lipsius criticized Coornhert for publishing their correspondence; ‘among the good it is the custom that letters written between two [men] perish with two. This sentiment, expressed by a man whose Centuriae of published correspondence spawned an entire genre, encapsulates the paradoxical rhetoric of Renaissance letter-writing and the friendship which it sustained; it was a seemingly private language geared (often) toward public consumption and use. And this unease is apparent in the preface of his first Centuria, where Lipsius professed to be ‘somehow willing unwilling' to publish the work. The publication of his later Ad Hispanos et Italos (1601), the first Centuria to appear after his reconciliation, was justified on account of the possible loss of the original letters - in other words, they were still published with the original recipient in mind. Lipsius also claimed that his letters offered general advice; ‘we offer counsel, warning, precautions, especially to young people, who I have always attempted to lead not just to pleasantries, [but] to usefulness, and to place them in mind and vigour above the common people'. The main aim of Lipsius' Centuriae, however, was to offer the reader a chance to get to know its author. Lipsius insisted on his sincerity: ‘not only (I am telling you the truth) do I not write twice, I hardly read them [my letters] twice. They emanate from me through a certain transparent channel straight from an open heart; they are as my mind or body is at the moment I write' ” (J. Machielsen, Friendship and Religion in the Republic of Letters; the Return of Justus Lipsius to Catholicism, 1591, in: “Renaissance Studies”, September 2011, pp. 4-5).

“From April 1583 to August 1585 Christopher Plantin had been living in Leiden and had established a second branch of his Officina. As soon as he was back in Antwerp, he realized that the political situation made it impossible to import or sell any works originating from the Leiden presses. On April 15, 1586 Plantin contacted Willem Breugel, member of the Council of Brabant and related to Lipsius. His Leiden partners had send him a few copies of Lipsius' Centuria prima, which he had submitted for approval to the responsible ecclesiastical book censors in Antwerp. Since they found no offence, he presented the Centuria to the States of Brabant, asking Breugel to insist that they t