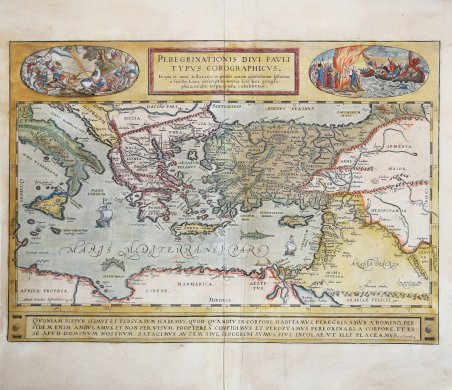

Magnifica mappa raffigurante la notevole estensione dei viaggi di San Paolo, che hanno attraversato la metà del mondo romano. È raffigurata la metà orientale del Mar Mediterraneo e la mappa si spinge a est fino a Babilonia. Tutte le città in cui si pensa che Paolo abbia viaggiato sono segnate sulla mappa. Splendida carta storico-geografica pubblicata nel ' Parergon ' di Abraham Ortelius. Esemplare dalla rara edizione italiana del Theatrum Orbis Terrarum stampata ad Anversa da Jean Baptiste Vrients nel 1608 e quindi nel 1612. In alto al centro il titolo: PEREGRINATIONIS DIVI PAVLI | TYPVS COROGRAPHICVS. | In quo et novi testamenti, in primis autem apostolorum historiae, | à Sancto Luca descriptæ, omnia ferè loca geogra:|phica, oculis inspicienda, exhibentur. Nell’angolo inferiore destro della mappa: Cum priuilegio Imp. | et Regiæ Maiestatis. Nell’angolo inferiore sinistro della mappa: Abraham Ortelius describebat 1579. Nel cartiglio inferiore: QVONIAM IGITVR SCIMVS ET PERSVASVM HABEMVS, QVOD QVAMDIV IN CORPORE HABITAMVS, PEREGRINAMVR A DOMINO; PER | FIDEM ENIM AMBVLAMVS, ET NON PER VISVM; PROPTEREA CONFIDIMVS ET PEROPTAMVS PEREGRINARI A CORPORE, ET ES:|SE APVD DOMINVM NOSTRVM. SATAGIMVS AVTEM SIVE PEREGRINI SVMVS, SIVE INCOLÆ, VT ILLI PLACEAMVS. "2. Corinth.5". Il medaglione in alto a sinistra mostra la conversione di Saulo sulla via di Damasco (Atti 9:1-9). Dio appare tra le nuvole e gli indirizza dei raggi di luce. Accecato, Saulo cade da cavallo e viene aiutato a rimettersi in piedi. Sullo sfondo a destra, due uomini conducono Saulo accecato a Damasco, che si intravede sullo sfondo. Il medaglione in alto a destra mostra il naufragio di Paolo sulla costa di Malta (Atti 27, 39-44). Vuylsteke (1984, Vol. 1, p. 132) non avendo individuato il modello iconografico per queste scene, suggerisce che potrebbero essere state disegnate da Ortelius stesso. Questa carta è stata realizzata da Ortelius sulla base della carta dell'Europa di Mercatore del 1554 e di una compilazione di carte che illustrano i viaggi di San Paolo da parte di Oronce Fine, Peter Apianus, Marcus Jordanus, Christian Sgrooten e B. Arias Montanus di Siviglia. Esemplare nel secondo stato di tre descritto da Van den Broecke, inserito nelle edizioni successive al 1592: “between 1587 and 1592, the entire plate was revised. The place name "Phestia" on the South coast of Crete was changed to "Phestû" and "Lazæa" was added on this South coast as well. On the coast of Palestina, "Ptolemais" was added; to "Heroum" on the Northern tip of the Red Sea "urbs" was added. "Balagea" on the river Euphrat was changed to "Balatœa" and "Belgijnea" near Babylon was changed to "Belgnæa". There were also numerous ornamental changes: coast lines were somewhat extended.The picture upper left received additional hachuring. especially below the horse front left; in the top right picture, the blank part upper right has now been filled in” (cfr. M. Van den Broecke, Ortelius Atlas Maps, n. 181). Circa una decade dopo la pubblicazione del “moderno” Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, Ortelius rispose alle “preghiere di amici e studiosi di storia antica, sacra e profana” e compilò una serie di mappe di soggetto biblico e classico, quasi tutte disegnate da lui. Intitolò l’opera “Parergon theatri”, ovvero “aggiunta, appendice, del Theatrum”, ma al tempo stesso anche complementare al Theatrum: il Paregon theatri forniva per il mondo antico lo stesso materiale che Ortelius aveva fornito per il mondo moderno con il Theatrum: carte geografiche. Lo spirito del Parergon è tutto riassunto nel motto historiae oculus geographia riportato sul frontespizio: la geografia è l’occhio della storia. Le mappe del mondo antico avevano lo scopo di “rendere più chiari gli storici antichi e i poeti”. Le mappe del Paregon sono di tre tipologie: antiche regioni; carte letterarie e carte bibliche. Come sottolinea Koeman “il Parergon deve essere considerato come lavoro pe. This richly decorative map shows the remarkable extent of the travels of Saint Paul that spanned fully half of the Roman world. The eastern half Mediterranean Sea is depicted, and the map reaches as far to the east as Babylon. All of the cities to which Paul is thought to have traveled are marked on the map. Wonderful historical map published in Abraham Ortelius' Parergon. Example from the rare Italian edition of Theatrum Orbis Terrarum printed in Antwerp by Jean Baptiste Vrients in 1608 and then in 1612. Title at the top cartouche: PEREGRINATIONIS DIVI PAVLI | TYPVS COROGRAPHICVS. | In quo et novi testamenti, in primis autem apostolorum historiae, | à Sancto Luca descriptæ, omnia ferè loca geogra:|phica, oculis inspicienda, exhibentur. Bottom right corner: "Cum priuilegio Imp. | et Regiæ Maiestatis". Bottom left corner: "Abraham Ortelius describebat 1579". Cartouche along bottom: QVONIAM IGITVR SCIMVS ET PERSVASVM HABEMVS, QVOD QVAMDIV IN CORPORE HABITAMVS, PEREGRINAMVR A DOMINO; PER | FIDEM ENIM AMBVLAMVS, ET NON PER VISVM; PROPTEREA CONFIDIMVS ET PEROPTAMVS PEREGRINARI A CORPORE, ET ES:|SE APVD DOMINVM NOSTRVM. SATAGIMVS AVTEM SIVE PEREGRINI SVMVS, SIVE INCOLÆ, VT ILLI PLACEAMVS. "2. Corinth.5". ' Made by Ortelius on the basis of Mercator's 1554 map of Europe, and a compilation of maps displaying St. Paul's travels by Orontus Fineus of Dauphine in France, Peter Apian, Marcus Jordanus, Christian Sgrooten and B. Arias Montanus of Sevilla. The medallion in the upper left shows the conversion of Saulus on his way to Damascus (Acts 9:1-9). God appears in the clouds and directs rays of light to him. Blinded, Saulus falls from his horse and is helped back to his feet. In the background to the right, two men lead the blinded Saulus to Damascus, which can be seen in the background. The medallion top right shows Paulus being shipwrecked on the coast of Malta (Acts 27: 39-44). The victims light a fire. When St. Paul throws extra wood into the fire, a snake bites his hand. He shakes it off into the fire without being hurt, which leads the by-standers to think he is divine (Acts 28: 1-6). Vuylsteke (1983, Vol. 1, p.132) cannot point to an example of these scenes and suggests that Ortelius may have designed them himself. Example of the second state of three of the plate, printed after 1592: “between 1587 and 1592, the entire plate was revised. The place name "Phestia" on the South coast of Crete was changed to "Phestû" and "Lazæa" was added on this South coast as well. On the coast of Palestina, "Ptolemais" was added; to "Heroum" on the Northern tip of the Red Sea "urbs" was added. "Balagea" on the river Euphrat was changed to "Balatœa" and "Belgijnea" near Babylon was changed to "Belgnæa". There were also numerous ornamental changes: coast lines were somewhat extended.The picture upper left received additional hachuring. especially below the horse front left; in the top right picture, the blank part upper right has now been filled in” (cfr. M. Van den Broecke, Ortelius Atlas Maps, n. 181). The Parergon is the first historical atlas ever published. It was initially conceived by Ortelius as an appendix to his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum but given the considerable success of these historical maps it later became an independent work and remained the main source of all similar works throughout the seventeenth century. Koeman wrote: “This atlas of ancient geography must be regarded as a personal work of Ortelius. For this work he did not, as in the Theatrum, copy other people's maps but drew the originals himself. He took many places and regions from the lands of classical civilization to illustrate and clarify their history, a subject very close to his heart. The maps and plates of the Parergon have to be evaluated as the most outstanding engravings depicting the wide-spread interest in classical geography in the 16th century." The Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, which is considered the first true modern "Atlas". Th. Cfr.

Find out how to use

Find out how to use