Rare and modern books

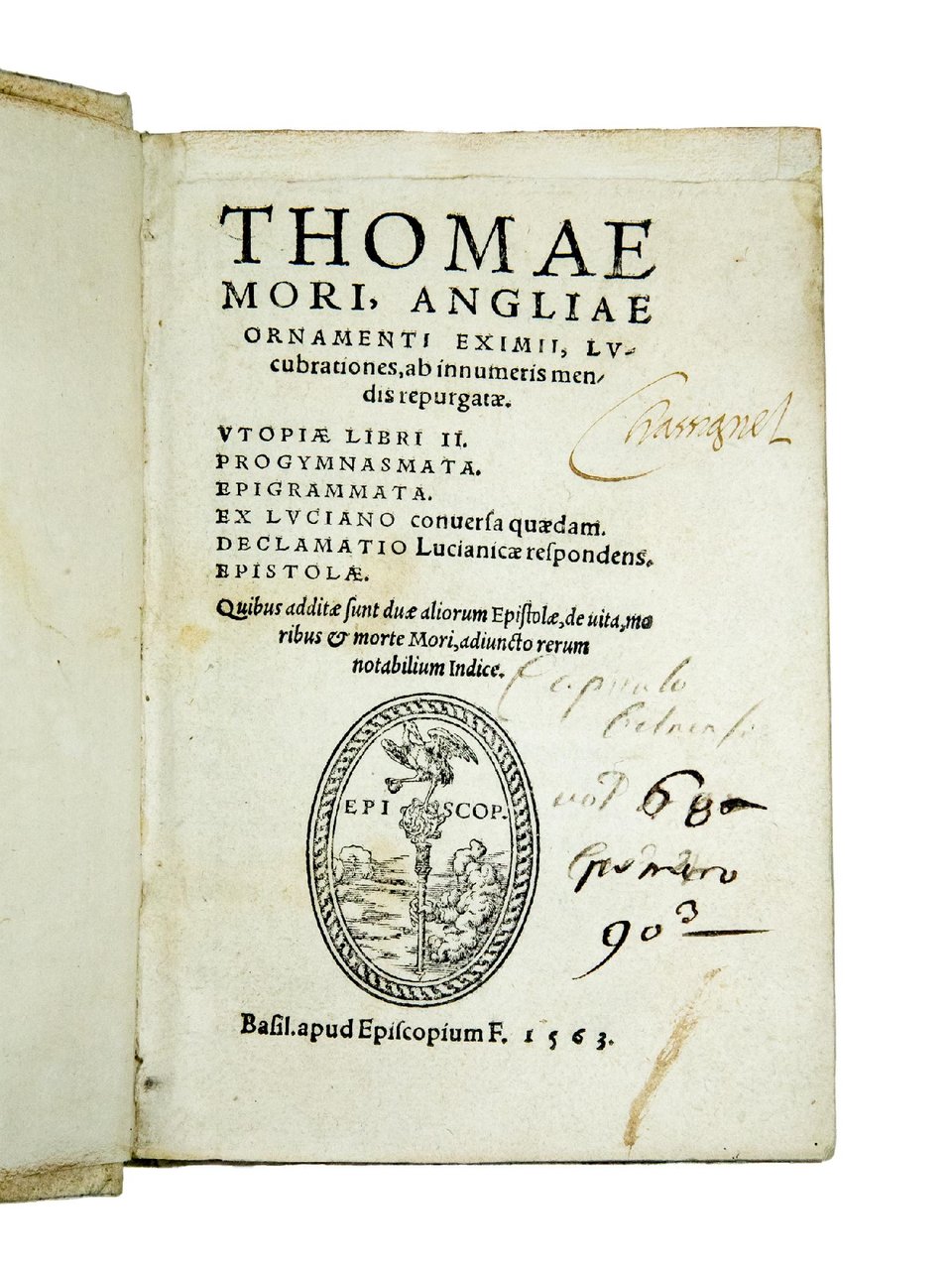

MORE, Thomas (1478-1535)

Lucubrationes, ab innumeris mendis repurgatae. Utopiae libri II. Progymnasmata. Epigrammata. Ex Luciano conversa quaedam. Declamatio Lucianicae respondens. Epistolae. Quibus additae sunt duae aliorum Epistolae, de vita, moribus et morte Mori, adiuncto rerum notabilium Indice

Nikolaus Episcopius, 1563

2800.00 €

Govi Libreria Antiquaria

(Modena, Italy)

The correct shipping costs are calculated once the shipping address is entered during order creation. One or more delivery methods are available at the Seller's own discretion: Standard, Express, Economy, In-store pick-up.

Bookshop shipping conditions:

For items priced over €300, it is possible to request an instalment plan from Maremagnum. Payment can be made with Carta del Docente, Carta della cultura giovani e del merito, Public Administration.

Delivery time is estimated according to the shipping time of the bookshop and the courier. In case of customs detention, delivery delays may occur. Any customs duties are charged to the recipient.

For more infoPayment methods

- PayPal

- Credit card

- Bank transfer

-

-

Find out how to use

your Carta del Docente -

Find out how to use

your Carta della cultura giovani e del merito

Details

Description

Adams, M-1752; VD 16, M-6302; R.W. Gibson, St. Thomas More: a Preliminary Bibliography of his Works and Moreana to the Year 1700, (Hamden, CT, 1977), no. 74; Th. More, The Correspondence, E.F. Rogers, ed., (Princeton, NJ, 1947), pp. XV-XXII; B.J. Trapp & H. Schulte-Herbrüggen, ‘The King's Good Servant': Sir Thomas More, Exhibition Catalogue, (London, 1977), p. 133, no. 261.

FIRST COLLECTED EDITION of Thomas More's Latin works, in which are printed for the first time some of his letters.

The volume includes the two books of Utopia with the usual prefatory letters by Erasmus, Guillaume Budé, Pieter Gillis, and by More himself; More's and Lily's Progymnasmata; the Latin epigrams; More's translation of the dialogues of Lucian, along with his Declamatio in response to the latter; 13 letters by More, 1 letter addressed by Erasmus to Ulrich von Hutten on More's life, and 1 letter on More's death generally attributed to Gilbert Cousin, Philippus Montanus, and Eramsus himself.

Among More's letters stands out the famous long letter to Martin Dorp at Louvain dated October 21, 1515 (pp. 365-428), which is, in fact, a vindication of the ‘new learning', and a clear statement of More's intellectual credo. He considered the study of the Greek text of the New Testament much more desirable than the blind acceptance of the Vulgate. This statement was of considerable importance for the development of humanism and of Western thought generally (cf. J.H. Bentley, New Testament Scholarship at Louvain in the Early Sixteenth Century, in: “Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History”, new series, II, 1979, pp. 53-79).

Erasmus' letter to Hutten (pp. 497-510; cf. P.S. Allen, ed., Opus epistolarum Des. Erasmi, Oxford, 1922, IV, no. 999, pp. 12-23), first published in his Farrago nova epistolarum (Basel, 1519), gives a biography of More and a detailed description of his physical appearance. The final letter (pp. 511-530), signed by Covrinus Nucerinus (clearly a pseudonym) and addressed to Philippus Montanus, a pupil of Erasmus, is concerned with More's trial and execution. It had appeared for the first time without place of publication and printer's name, but had actually been printed by Hieronymus Froben in Basel in 1535 (cf. P.S. Allen, ed., Opus epistolarum Des. Erasmi, Oxford, 1947, XI, app. XXVII, pp. 368-378).

“Only ninety-three of More's Latin letters (among them four written under pseudonyms) survive, counting the familiar, the public, and everything in between […] Some of More's letters were suppressed, lost, or destroyed for political reasons, which makes the recent discovery of a manuscript bundle that belonged to Frans van Cranevelt and includes seven hitherto unknown letters by More an extraordinary event. But More himself, in this respect unlike Erasmus, does not seem to have tried to publish his letters (or have them published) as a collection, although clearly he kept copies. In fact, on occasion he withheld publication. In 1520, for instance, he wrote William Budé and asked him not to publish his letters to him, at least until he had revised them, […] In any case, More's situation differed from someone like Erasmus, despite his connections with him. More wrote some of his best-known familiar letters (and most of his official letters) in English, not Latin. Additionally, he was a busy lawyer, judge, administrator, and statesman; humanism was never the whole of his life, and his projections of self and life are multiple, even disparate. To put this another way, More depended much less than Erasmus did upon representing himself as a man of letters, although he was attracted to that sort of life. In fact only twenty-four of More's letters were published – that is, printed – during his lifetime, a